Unit 3 - Data cleaning and preprocessing

Data cleaning and preprocessing¶

Most data you’ll encounter contains extremely useful information and information that you don’t really need or that is actually noise. Cleaning and preprocessing allows you keep the useful information. It also puts the data in formats that will be easy to process by python and other programs.

File Processing¶

To understand file processing and encodings read the file manipulation tutorial which will give an overview of all of the techniques and functions you will be using: file manipulation

Opening a file using the with open() as will store the opened file in a data type that we can then use to read the file contents and store the contents to a variable. I will demonstrate how to open a file and save the contents to a string variable. The open() function takes two inputs: first the name of the file, and second whether you want to read (“r”) or write (“w”) to the file.

First let’s create our own text file in the data folder. You should have a folder called ‘data’ from last week, which contains the Ghostbusters script. Go to that directory, and create your own text file there. Using notepad create a file with some text in it and save it inside the data folder. I’ve done this and called my file ‘sample.txt’.

If you don’t have the ‘data’ folder, navigate to the directory where this notebook sits (remember you can use pwd to find it) and create a new directory, called ‘data’. Then, create a text file inside called “sample.txt”.

Write something in that file.

Now read through the code block to see how you can open and read this file.

To learn more about filepaths read the following chapter up to and including the “Absolute vs. Relative Paths”: https://

# create a variable to hold the path to the file

filePath = "./data/sample.txt" #relative path

# filePath = "C:/Maite/MOD/notebooks/Ling380/data/sample.txt" #absolute path

# open the file as "r" or read only and store this opened file in f

with open(filePath, "r") as f:

# read the data from f and store it in the string variable "data"

data = f.read()

# we can now print the data

print(data)pwd# create a variable to hold the path to the file

#filePath = "./data/sample.txt" #relative path

filePath = "C:/Maite/MOD/notebooks/python_text_analysis/data/sample2.txt" #absolute path

# open the file as "r" or read only and store this opened file in f

with open(filePath, "r") as f:

# read the data from f and store it in the string variable "data"

data = f.read()

# we can now print the data

print(data)Encoding¶

The instructions above helped us open a file that is in plain text format. You can use the same instructions to open the Ghostbusters file from last week, because it’s also in plain text format.

Most text, however, has more advanced information. This includes things like curly brackets and apostrophes (instead of straight quotes), but also accents, umlauts, emoji and many other special characters that plain text cannot handle. Then you need to use other forms of encoding, ways to store information that goes beyond the simple character. Character encoding maps characters to numerical representations.

ASCII¶

ASCII, which stands for American Standard Code for Information Interchange, is a pioneering character encoding system that has provided a foundation for many modern character encoding systems.

ASCII is still widely used, but is very limited in terms of its character range. If your language happens to include characters such as ä or ö, you are out of luck with ASCII.

Unicode¶

Unicode is a standard for encoding text in most writing systems used across the world, covering nearly 140,000 characters in modern and historic scripts, symbols and emoji.

For example, the pizza slice emoji 🍕 has the Unicode “code” U+1F355, whereas the corresponding code for a whitespace is U+0020.

Unicode can be implemented by different character encodings, such as UTF-8, which is defined by the Unicode standard. If you don’t know the encoding of your text, it is a good bet that it is in UTF-8.

Don’t think that Unicode is only for foreign accents or emoji. Even in plain English, whenever you change from straight quotes to curly quotes (aka smart quotes), you are using Unicode. Note the difference in the quotes and the apostrophe in the two sentences below.

Practice¶

Let us know try and see what happens if we read text that is encoded in UTF-8 as plain text. Go to Radio Canada and copy the first paragraph of the first article you find there. Save it in a text file in the data directory, let’s call the file “radio-canada.txt”. Now, try to read the file and print it on screen. What do you see?

# create a variable to hold the path to the file

filePath = "./data/radio-canada.txt"

# open the file as "r" or read only and store this opened file in f

with open(filePath, "r") as f:

# read the data from f and store it in the string variable "data"

data = f.read()

# we can now print the data

print(data)Now do the same thing, but add the flag encoding="utf-8" to the open command. What is the difference in the output?

# create a variable to hold the path to the file

filePath = "./data/radio-canada.txt"

# open the file as "r" or read only and store this opened file in f

with open(filePath, "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

# read the data from f and store it in the string variable "data"

data = f.read()

# we can now print the data

print(data)File formats¶

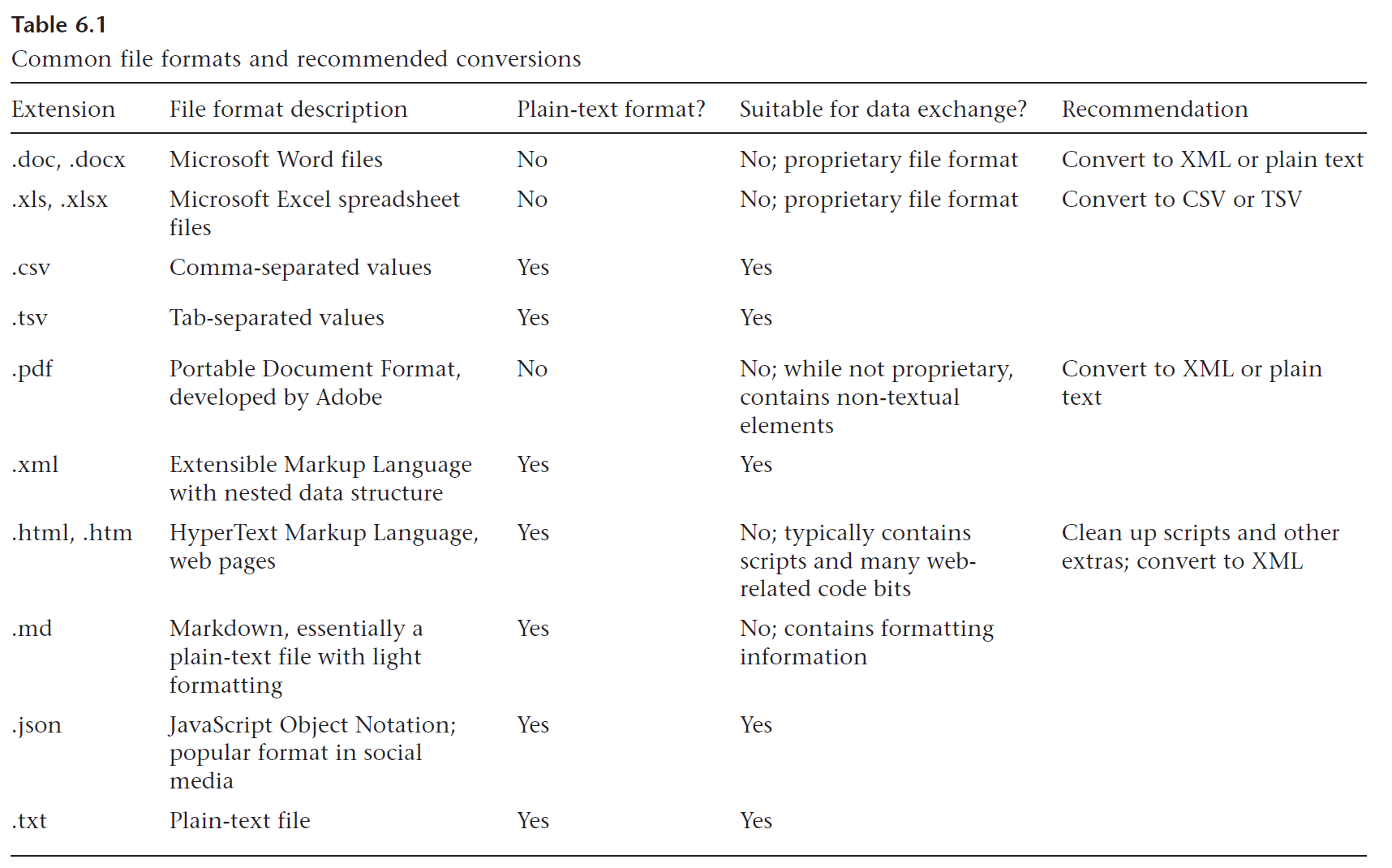

ASCII and UTF refer to the encoding of the text itself. In addition, files can have different formats, usually represented by their extension (.docx, .csv, .pdf, etc.). The extension tells the operating system which application to use to open the file.

For data processing, different extensions (= different file formats) have different properties. The table from the article by Han (2022) is a nice summary of their properties. We will most often deal with plain text formats that are suitable for data exchange, including: .txt, .csv, .xml, and .json.

Common file formats, from Han (2022), https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12200.003.0010

Tip: if you want to see the file extensions on your system, you can change the options in Windows or Mac so that you can see them in Explorer/Finder.

Writing to a file¶

Now that we know about file formats and about reading from files, let’s do one last exercise, printing to a file. We’ll work with the Ghostbusters file from last week. First, we’ll read it into a variable. Then, we’ll count the number of words in it (tokens) and we’ll write that information to a csv file.

This is a very simple way of counting words, and it will count both actual words and punctuation or numbers. We’ll learn how to do this more smartly, using NLTK.

# create a variable to hold the path to the file

filePath = "./data/Ghostbusters.txt"

# create a variable to hold the word counter

# set it to 0

n_words = 0

# open the file as "r" or read only and store this opened file in f

with open(filePath, "r", encoding="utf-8") as f:

# read the data from f and store it in the string variable "ghostbusters"

ghostbusters = f.read()

# use the split() function, to split text at spaces

lines = ghostbusters.split()

# create a variable, n_words, and add to it every time the lines counter increases

# note the += This reassigns the value of lines to n_words (=) and increases it (+)

n_words += len(lines)

# Print the final value

print(n_words) # import the csv library, to manipulate csv files

import csv

# create a new file in csv format

with open('./data/file_lengths.csv', 'w') as out:

# create file writer object

writer = csv.writer(out)

# the first row creates headings

writer.writerow(['file', 'length'])

# write the name of the file and the length in the second row

writer.writerow([filePath, n_words])Intro to NLTK¶

NLTK (Natural Language ToolKit) is a light-weight (but still quite powerful) NLP tool. You can learn more about it from the NLTK website and the NLTK book.

If you haven’t installed NLTK yet, go to the nltk_install.ipynb notebook in the Python for text analysis notebook or repository and run it. Then come back here. The next cell just imports all the libraries that we need.

import nltk

from nltk.tokenize import word_tokenize

from nltk import FreqDistWe are going to use the text we read in above, which should be in the variable ghostbusters. We will tokenize that text, that is, convert the string of text into a list of words and punctuation (aka tokens). When you print below, note the format of the list, with tokens in quotes (because they are strings) and separated by a comma.

# use the word_tokenize function from NLTK

tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(ghostbusters)

# just check what the variable contains

print(tokens)Now let’s say I’m interested in how many tokens this script contains. I can use the built-in python function len() to find that out and store it in the variable n_tokens.

n_tokens = len(tokens)

print(n_tokens)That was the tokens, i.e., the words and punctuation in the script. That’s going to include repeated instances of each token. There’ll be many instances of the type “the” or “.”. Types refers to the unique tokens. To find how many types or unique tokens the text has, we use the set() function and assign the result to the variable n_types.

n_types = len(set(tokens))

print(n_types)There is another interesting feature of text, the lexical diversity. Lexical diversity just measures how many unique words are used with regard to how many total words there are. This is an interesting measure, for instance, for children’s books. You want to have a relatively low lexical diversity, so that young readers are not overwhelmed by too many (potentially new) words.

lexical_diversity = n_types / n_tokens

print(lexical_diversity)Finally, an interesting thing you can do with a file is to create a dictionary of all the tokens in the text and count how many times they appear. NLTK does this with the FreqDist function (frequenty distribution).

Note that the output of the function is a dictionary. A dictionary in python has the following structure:

{ key1: value1,

key2: value2,

key3: value3,

etc.

}The dictionary created by FreqDist() has a word as a key and the frequency of that word as the value. Note that the words are in single quotes, because they are strings.

freq_dist = FreqDist(tokens)

freq_distReading multiple files in a directory¶

So far, we have read one file at a time. But that’s not really useful when you want to process lots of data. Here, you’ll learn to use the os library to read all the files in a directory, or all the files of a certain type (e.g., .txt files).

The os library allows you to work with the files in your system the way you’d do in Explorer/Finder, but from inside the notebook. This short introduction explains how to get the current directory, make a directory, and change directories.

Here, we will only use the functions that allow us to read many files. You can see an explanation on how to read multiple files from a folder. The basics:

import the os library

assign the path where you want to read files from

use the os.path.join() function to get all the filenames

do a for loop to go through all the file names

do something with those file names (here, read them into a variable)

# import the library

import os

# define the path

# I'm trying to always use "data" as the place to store texts

path = './data'

# loop through all the files in the directory "data"

for filename in os.listdir(path):

# check only for .txt files

if filename.endswith(".txt"):

# get all the filenames with a .txt extension

file_path = os.path.join(path, filename)

# open one file at a time, to read it, and with utf encoding

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding="utf-8") as f:

# store the contents of the file into the variable "text"

text = f.read()

# the next 2 statements are just a check

# print the name of the file and the first 50 characters

print(f"File: {filename}:")

print(text[:50])Now that we have read the files, let’s modify that function to count the tokens and print that information. I’ll modify the code above to:

create a dictionary to store the tokens

tokenize each text as I read it

store the length of the tokens in the dictionary

You’ll need to expand this in the lab.

# import the library

import os

# define the path

# I'm trying to always use "data" as the place to store texts

path = './data'

# create an empty dictionary. Note the curly brackets

tokens_files = {}

# loop through all the files in the directory "data"

for filename in os.listdir(path):

# check only for .txt files

if filename.endswith(".txt"):

# get all the filenames with a .txt extension

file_path = os.path.join(path, filename)

# open one file at a time, to read it, and with utf encoding

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding="utf-8") as f:

# store the contents of the file into the variable "text"

text = f.read()

# tokenize the text using NLTK

tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(text)

# store the length of the variable tokens into tokens_files

tokens_files[filename] = len(tokens)Print the results. After the for loop above has completed, the dictionary tokens_files contains the name of the file and the length in tokens. You can print it to the screen.

tokens_filesIt’s even better if you can save this in a csv file, reusing some of the code above. Then, you always have that information and don’t have to run this notebook to get it.

We are going to do something a little different than above for the csv information. Since we may eventually have lots of information for each file (tokens, types, lexical diversity, etc.), we’ll first create a list with all the information and then we’ll save it to the csv file.

# remember that you have to import the csv library, if you haven't run this from the beginning

import csv

# create an empty list

file_info = []

# save all the information from above in this list

for filename in tokens_files:

file_info.append([

filename,

tokens_files[filename],

])

# create a csv file to store the information. I also like to put it in "data"

output_csv = './data/file_info.csv'

with open(output_csv, 'w') as out:

# create file writer object

# the delimiter is what is used to separate data into columns, in this case a comma for csv

writer = csv.writer(out)

# the first row creates headings

writer.writerow(['file', 'tokens'])

# write the rest

writer.writerows(file_info)Summary¶

In this notebook you have learned some concepts about processing text and how to deal with language data. Review the notebook and make sure you understand them:

tokens

types

lexical diversity

frequency distribution

You have also learned a few new things about python:

2 new data types: lists and dictionaries

encoding in ASCII and UTF-8

how to read in the contents of a file

how to write to a csv file

how to read all the files in a directory

And, finally, you have also learned how to use some of NLTK’s functions.

Acknowledgments¶

Parts of this notebook were adapted, with thanks, from a course by Tuomo Hiippala at the University of Helsinki.

- Han, N.-R. (2022). Transforming Data. In The Open Handbook of Linguistic Data Management (pp. 73–88). The MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/12200.003.0010